Seeing The Lindisfarne Gospels is a ‘spine-tingling’ moment

The Lindisfarne Gospels are back in their native north east.

The manuscript, produced in the Northumberland island monastery of Lindisfarne at the end of the seventh century, is considered one of the nation’s greatest treasures.

A unique relic of early Christianity in England, it is so precious that the British Library only loans it out at least every seven years – and strict rules govern the exposure of its pages.

Having visited the region in 1987, 1996, 2000 and 2013, the Lindisfarne Gospels are currently on show at the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle.

A region ‘Inspired by Lindisfarne’

Both of my weekly calligraphy groups have seen the exhibition as part of our Inspired by Lindisfarne project, which is supported using public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England. You can read more about it here.

The exhibition takes over four rooms on the first floor of the building, while a complementary exhibition, These Are Our Treasures, resides on the ground floor.

The first room features an immersive digital installation designed by NOVAK, with a slideshow of images filling the walls as the story of the Lindisfarne Gospels is told amidst the sound of crashing waves and sea birds.

This colourful display gives way to the darkness of the second room, where the Lindisfarne Gospels are held, alongside other ancient manuscripts and rare treasures that tell the story of how Christianity arrived in Anglo-Saxon England.

Ancient manuscripts reveal their secrets

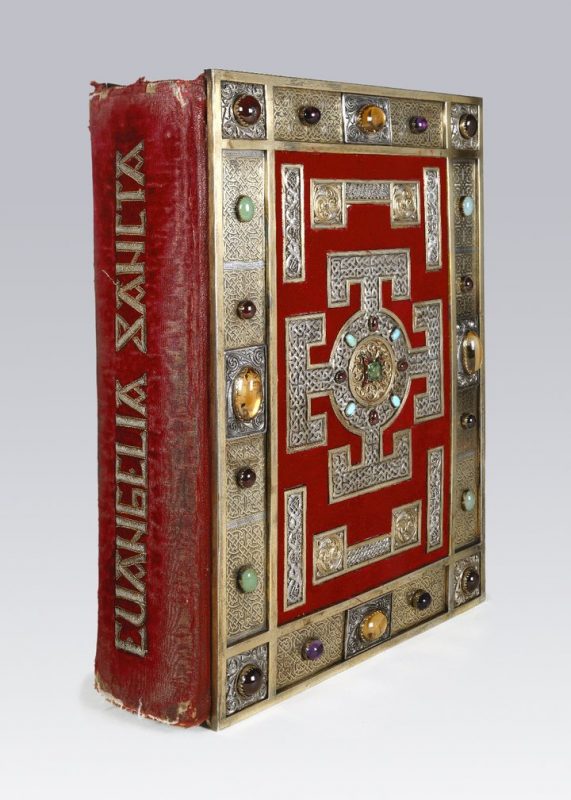

Among them is the St Cuthbert Gospel, another native north east manuscript, created at the twin monasteries of Wearmouth-Jarrow in the early eight century.

It was found inside St Cuthbert’s coffin when it was opened in 1104, after being moved to Durham Cathedral, and is the earliest European book with an original, intact binding.

Other manuscripts on show include The MacRegol Gospels, The Tiberius Bede, The MacDurnan Gospels and The Ortho-Corpus Gospels, of which only three fragments exist after it was split into two parts in the 16th century.

I particularly liked that you could see where lines had been ruled on the page ready for text before it became an illustrated page, depicting an eagle as a symbol of St John and bold geometric forms of protective crosses.

Other items on display include stone crosses featuring Christian and Pictish imagery, such as bird-headed figures, beasts and monsters, the Trumpington cross and linked pins and a cross pendant from the Staffordshire Hoard.

The Lindisfarne Gospels take centre stage

Having taken in all of these fascinating objects, it’s easy to forget the reason for the exhibition – until it suddenly comes into view.

The Lindisfarne Gospels are displayed towards the back of the room in a tall glass case, with a custom-made stand supporting the spine and jewelled covers.

(NB. You have to be a bit of a contortionist if you want to see the cover.)

The book is open at the St John’s Gospel carpet page – the last piece of major decoration in the book – and seeing it in person is certainly a spine-tingling moment.

What I’ve learned about The Lindisfarne Gospels

I have learned a lot about the Lindisfarne Gospels over the last month as a result of the activities surrounding their visit to the region and they are certainly awe-inspiring.

All 518 pages were scribed by just one hand, that of Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne, in honour of St Cuthbert, a monk, bishop and hermit, who died in 687.

It was bound by Bishop Ethelwald of Lindisfarne, who succeeded Eadfrith in 721, decorated by Billfrith the anchorite and translated in the mid-10th century by Aldred.

I was surprised that Celtic, Germanic and Mediterranean influences can be seen in the decoration of the Lindisfarne Gospels, as well as the writing, which also features the early Irish language alphabet, Oghum.

The Lindisfarne Gospels were produced on calf-skin vellum (50 skins were required in total) and the ink was made from oak galls and applied with a feather quill cut to pen length, although brushes were also used.

Pin prick marks in the pages and lead point sketches show how the layout was planned and renowned calligraphy Patricia Lovett, who gave an online talk for Northumberland Archives about The Art and Craft of the Lindisfarne Gospels, believes there was a system for backlighting using glass and candles.

There are 90 identifiable colours in the Lindisfarne Gospels, made from six pigments.

A modern take on art and spirituality

The third room of the exhibition houses Seeing Deeply: Spiritual Art Across Centuries, which explores the relationship between art and spirituality and its development since the creation of The Lindisfarne Gospels.

I loved the collection of contemporary work on display here, the most recent being Zarah Hussain’s neon geometric patterns Inhale IV and Exhale IV.

In This Space We Breathe, by Khadija Saye, makes you stop and think, not only about the stark black-and-white images, but also the tragedy of the Gambian-British photographer losing her life in the Grenfell Tower fire, aged just 24.

The final room is easy to miss, but take a sharp right from the final gallery and you’ll find Jeremy Deller’s film, The Deliverers.

The Turner Prize-winner filmed at the British Library and in Newcastle, showing the Lindisfarne Gospels being carefully packed and transported (in quite an unusual and trippy sort of way) north to the exhibition, which runs until December 3.

For more information about the exhibition and the programme of events around it, visit the Laing Art gallery website here.